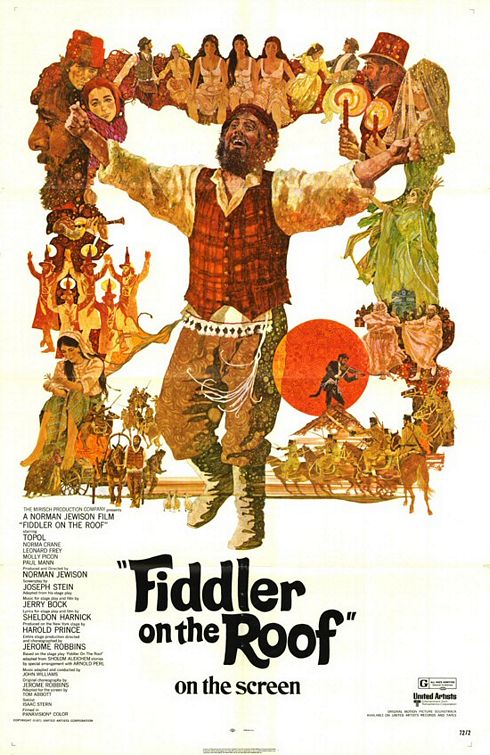

dir. Norman Jewison

If this isn’t a perfect musical, then the category may need to be redefined. It has scale, humor, heartbreak, and songs that arrive not with pomp but with the inevitability of folk wisdom. Topol, in the role of Tevye, is a revelation—not just because he sings and dances with effortless verve, but because he filters every comic beat through a weathered kind of warmth. There’s a slight squint in his gaze, a shrug in his voice (the expressive kind, not the banned metaphorical one), and the sense that fantasy is the only insulation he’s got left against a world that keeps rewriting the rules. It would have been a treat to see Zero Mostel reprise the role he originated, but Topol more than earns his place here. He grounds the performance in something weary and sly, and the humor becomes less about punchlines than survival instincts. His scenes with his daughters are the beating heart of the film—especially with Tzeitel (Rosalind Harris), whose insistence on marrying for love nudges the entire narrative into motion. Tevye’s reaction, both proud and bewildered, is summed up in one of the film’s best lines: “They’re so happy, they don’t know how miserable they are.” The songs are astonishing—richly melodic, seamlessly integrated, and remarkably resistant to age. There isn’t a weak one in the bunch, and several (If I Were a Rich Man, Matchmaker, Do You Love Me?) have reached that rarified status where they feel like they’ve always existed. The first half of the film hums with energy and warmth, but it gradually darkens as the story catches up with history. The second act makes you earn your joy back in installments. One musical number arrives with such emotional precision it practically wrings the tears out of you on cue. Norman Jewison directs with a steady hand, balancing stage origins and cinematic scale. The camera occasionally cranes, occasionally lingers, but mostly it gets out of the way and lets the material sing. There’s no effort to gloss over the hardship or erase the politics—the film understands that Tevye’s humor exists precisely because it has to. What begins in song ends in exile, but what stays with you isn’t the displacement—it’s the rituals, the dances, the stubborn insistence on dignity.

Starring: Topol, Norma Crane, Leonard Frey, Molly Picon, Rosalind Harris, Michele Marsh, Neva Small, Paul Michael Glaser, Raymond Lovelock.

Rated G. United Artists. USA. 181 mins.